8 Afghanistan vets look back in anger — and pride — over America’s longest war

by Heather Robinson

From The New York Post

One year after the US pulled out of Afghanistan, former soldiers Florent Groberg (left), Pete Hegseth (center) and Amber Smith reflect on their time serving in America’s longest war. Getty Images/iStockphoto

Over two decades, 775,000 soldiers and Marines were deployed to Afghanistan before the Biden administration’s abrupt and chaotic withdrawal one year ago. Now, many who served look back at their time with mixed emotions.

Some remember that the war began as a response to 9/11, and feel proud that the US decimated al Qaeda, who launched that brutal attack with help from the Taliban in Afghanistan. Others lament the folly of a nation-building project that ultimately failed.

Some lost friends and limbs. All of them risked their lives. Here, eight members of the military — from different ranks, branches and backgrounds — told The Post about their personal experiences serving in America’s longest war.

US Army Capt. Florent Ahmed Groberg, 39, Medal of Honor Recipient, Microsoft executive.

Army Capt. Florent Groberg receives the Medal of Honor from President Barack Obama in November 2015. AFP via Getty Images

Tours of duty in Afghanistan: November-June 2009; February 2010-August 2012

Florent Groberg had to think fast.

While protecting 28 Afghan and American leaders in Asadabad, he saw two motorcycles speeding toward him. At the same moment, a dark-robed male figure caught his eye.

Groberg sensed danger. The motorcycles stopped. They were a decoy; the man was a threat. But Groberg, a trained Army Ranger, did not shoot because he did not see a weapon.

Groberg (left) on watch with a fellow soldier in Afghanistan, where he saved lives by hurling away a suicide bomber just before the terrorist’s vest exploded.

Instead, he rushed toward the man and grabbed him, feeling a suicide bomber’s vest underneath his robe.

“My instinct told me to get him away from everyone as quickly as possible.”

With all his strength, Groberg hurled the terrorist as far away as he could.

The man landed, detonating his suicide vest and killing four — far fewer than if he had reached the leaders — and badly injuring Groberg, who would undergo multiple surgeries before he could walk again.

For his courage that day, President Barack Obama awarded Groberg the Medal of Honor, the military’s highest award for valor in combat.

Born to an Algerian Muslim mother in France and adopted by an American stepfather, Groberg is the only immigrant to receive this honor in America’s post-9/11 wars.

Fury over the murder of his favorite uncle, Abdou, a peaceful Algerian Muslim preacher, by radical Islamists, and the attacks of Sept. 11, sparked his desire to serve. Seven months prior, he had become an American citizen.

Born in Algeria, Groberg yearned to serve America because it “welcomed me,” he said.

“This country welcomed me and gave me the honor and responsibility to call myself an American,” said Groberg. “I felt I better go earn it.”

But the handling of America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan dismayed him.

“I didn’t expect us to stay there forever,” he said. “But the way it happened was disheartening. It was frustrating to see all that work unravel.”

Still, he is optimistic about the future.

“I do believe we influenced the next generation of Afghan leaders,” he said. “We opened schools for girls, they became educated, and I’m confident that what we did will help shape the course of life in that country in coming decades.”

Today Groberg works for Microsoft supporting creation of technologies to help the Defense Department, intelligence communities, and law enforcement.

Daniel Patrick O’Shea, Ret. Navy Seal, counterinsurgency advisor, 55; business management, Tampa, Fla.

Former Navy SEAL Daniel Patrick O’Shea with an Afghani elder during his 2011-2012 tour of duty.

Tours of duty in Afghanistan: November 2007-January 2008; December-April 2010; September 2011-September 2012

On August 16, 2021, desperate Afghans were clinging to the sides of US aircraft departing Kabul. Four thousand instant messages and texts begging for help streamed over Dan O’Shea’s phone.

A valued Afghan operative, “Abdul,” who had assisted US forces in fighting a major terror network, was now being hunted by the Taliban. O’Shea focused on him first.

Ten years before, O’Shea had been received as a “graybeard” — a man of honor — at “goat grabs,” or traditional meals of goat meat and fruit, in the homes of Afghan leaders who believed in the dream of democracy.

“Because I was 45 and a ‘graybeard,’ they’d sit me in a position of honor. If you make it to your 60s in Afghanistan you are a true elder.”

Now “Graybeard” was back in the US but still springing into action.

Dubbed “Graybeard,” the 55-year-old Navy vet joined a volunteer force that helped extract Americans and Afghan allies during the withdrawal, including three generations of one family.

Working with Task Force Pineapple, a volunteer group of US veterans trying to evacuate Americans and Afghan allies, he came up with a plan.

The gates leading out of Kabul were closing. Colleagues there helped O’Shea direct Abdul out, but because he was unwilling to leave without his family, each attempt failed. Although Abdul possessed a US passport, his family members did not.

O’Shea knew one way out was through sewage channels, but Abdul’s family included a set of three-month-old twins, so that was out.

Considering dwindling options, O’Shea texted Abdul, “You have to make some tough choices about who you can bring.”

O’Shea’s voice trembles as he recalls receiving this text: “‘Dan, my father raised me to be the man I am. I’m not leaving him, my mother, my sisters or their children. Would you?’”

“I wrote that I wouldn’t either.”

“Abdul answered, ‘If we die, we die as a family.’”

Reading that, O’Shea redoubled his efforts to do the impossible. Tech-savvy and tenacious, he managed to create and send a document that convinced Afghan soldiers fearful of the Taliban to allow Abdul’s entire family to board a bus to the airport.

After they made it out, Abdul texted O’Shea:

“Thank you, Dan. You saved three generations of my family.”

One year later, O’Shea is still angry about our “abandonment” of the Afghan people.

“There are hundreds of US vets trying to get Afghan partners out who are being hunted by the Taliban, and we are being stonewalled by the US State Department. Afghan soldiers and partners, Afghan women and girls, who believed in the dream we gave them for 20 years — America threw them under the bus.

“We buried brothers and sisters over there and now we have to ask, ‘For what?’”

O’Shea is currently a partner in Equitus Corp., an analytics and data company based in Clearwater, Fla., providing technology to the Department of Defense.

US Army Combat Pilot Amber Smith, 39; author, Texas

Pilot Amber “Annihilator 24” Smith in the cockpit of her Kiowa Warrior helicopter, where she rained fire on Taliban fighters.

Tours of duty in Afghanistan: January 2008-July 2008; July 2008-December 2008

Amber Smith could see the enemy poking their heads out of a cave in Asadabad. From the cockpit of her Kiowa Warrior helicopter — a small single engine craft that enabled her to get within hundreds of feet of the Taliban — she took aim at the mouth of it.

She fired one rocket, which exploded against the rocks. Then another.

“I wanted to be judged on merit and skill and nothing else,” said Smith, who wrote a book about her more than 100 combat missions, “Danger Close.” AP

As she began to turn, a huge explosion shattered the quiet. Her second rocket had been a perfect shot, penetrating deep into the cave and destroying scores of Taliban fighters.

Smith, whose call sign was “Annihilator 24,” was frequently called in when ground forces were under attack.

Being a woman in combat did not faze her. “I wanted to be judged on merit and skill and nothing else, and ultimately, I think I was.”

Smith (left) with her older sister Kelly, who is an Air Force pilot, at Bagram Air Base in 2008.

Given her efforts and those of fellow service members, she was saddened by last year’s pullout.

“We devoted years and risked our lives for the mission. It was very difficult for us to watch.”

Today a wife and mother of two, Smith — who flew more than 100 combat missions in her military career — is the author of “Danger Close: My Epic Journey as a Combat Helicopter Pilot in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

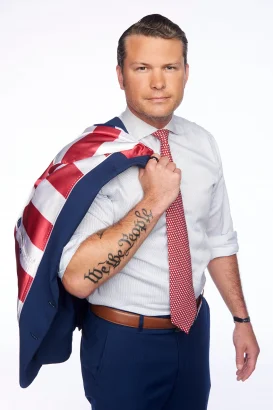

US Army Capt. Pete Hegseth, 42; Television host, author

Army Capt. Pete Hegseth felt the call to serve after visiting a still-smoldering Ground Zero in 2001, declaring, “Now is the time to go kill terrorists.”

Tour of duty in Afghanistan: 2010-2011

As an undergraduate at Princeton, Pete Hegseth was angered by students protesting any response to the attacks of Sept. 11.

“We had thousands of Americans dead from a cowardly terror attack, and these elitist, sheltered students were protesting as if the real victims here were misunderstood Islamists,” he said.

Days later, he visited the World Trade Center site and witnessed the smoldering destruction.

“I felt, ‘Now is the time to go kill terrorists,’” he remembered. The tragic scene only reinforced his earlier decision to join ROTC.

In Afghanistan, Hegseth’s task was to train Afghan and NATO soldiers to counter the efforts of the Taliban and al Qaeda to win over the local population.

But, for various reasons, he believes it was an unrealistic goal.

He thinks that introducing “Western-style social justice” including women’s rights was counterproductive.

“It would be great if full female empowerment was part of their culture, but it’s not, so by pushing it, you create more propaganda for the Taliban.”

While he believes the war “should have ended 10 years ago,” he took issue with what he sees as a lack of planning and toughness in the way President Biden ended it. And he is disgusted to see the Taliban celebrating in Kabul’s streets a year after the US withdrawal.

Hegseth (left) trained Afghan and NATO soldiers to help oust the Taliban, a group of “drug runners and thugs” who don’t respect women’s rights, he said. Coscia, Alexandra

“Anyone who thought there was a Taliban 2.0 is a fool. There is no Taliban that supports women’s rights. They are drug runners and thugs. They will shut down every Western idea we had and conform to the strictest code of Islam. Evidenced by the fact Ayman al-Zawahiri [an architect of the 9/11 attacks] was killed in Kabul, the Taliban is still working with al Qaeda.”

Hegseth is now co-host of “Fox & Friends Weekend” on Fox News Channel and author of “Battle for the American Mind.”

Staff Sgt. Johnny Joey Jones, Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technician, USMC, 36; Fox News contributor and Fox Nation host, Newman, Georgia

Staff Sgt. Johnny Joey Jones with new knees and legs at Fox News.

Tour of duty in Afghanistan: March 15-August 6, 2010

On Aug. 6, 2010, Johnny Joey Jones, 24, stepped on an Improvised Explosive Device (IED) that ripped his legs off from his knees. It also took the life of Kristopher “Daniel” Greer, a corporal who had been assisting Jones as a combat engineer.

“In every step of Daniel’s life, he served,” said Jones of the husband, father, and firefighter who died that day at age 25.

Jones’ childhood in Georgia was “very poor and happy.” He became a Marine because he wanted to be a “better version” of himself — and serve his country after Sept. 11.

Jones (right) successfully disabled 78 explosive devises before being blasted by one that severely injured him and killed combat engineer Kristopher “Daniel” Greer.

He volunteered for Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) school, which includes a rigorous academic program of mechanics, chemistry and physics.

“The Marine Corps wants people for EOD whose thirst for knowledge and willingness to sacrifice are a cut above,” said Jones, adding that many of the best and brightest were lost.

“This 20-year war just destroyed our numbers.”

He is proud of having disabled 78 IEDs before he was gravely injured by one. “I had the chance to use my knowledge and put my life on the line so fewer lives and limbs were lost to our service members and the Afghan people.”

Looking back, he believes American policymakers were blind to the folly of nation-building in Afghanistan.

“Optimism can become hubris if you’re not looking with clear eyes.”

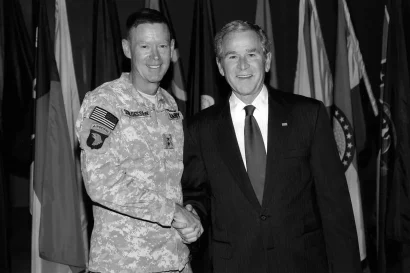

Ret. US Army Major Gen. Jeff Schloesser, former commander of the 101st Airborne Division, business executive, Washington D.C.

Former Army Major Gen. Jeff Schloesser served 14 months in Afghanistan, commanding the vaunted 101st Airborne Division and helping train Afghan soldiers to fight the Taliban. AFP via Getty Images

Tour of duty in Afghanistan: April 2008 – June 2009

Gen. Schloesser served as commander of the Army’s 101st Airborne Division in Eastern Afghanistan, making daily decisions about sending soldiers into battle. Under his command, 184 were lost.

“I have never forgotten them, and never will,” he said.

He stressed the value of US intervention in Afghanistan as part of the War on Terror.

Schloesser, who briefed President George W. Bush on the war’s progress, believes the US should have started to pull out of Afghanistan after Osama bin Laden was killed.

“The American people can look back on the last two decades and see they have not been attacked as we were on September 11th,” he said.

America’s failure to empower Afghans to vanquish the Taliban may have reflected cultural differences, he added.

“We tried to make them soldiers in a Western way, and I don’t think we were successful,” he said. “But if you asked them to fight for their tribe … they did well.”

Schloesser, who briefed Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama on the war’s progress, acknowledged asking Obama for more troops and resources in 2008 (“He took it to heart and responded”).

But he cited what he sees as a lack of “strategic leadership” after the US killed Osama bin Laden.

“I think we should’ve started a strategic withdrawal of major forces then.”

Schloesser is pictured with Commander Shoshana Chatfield at her command in Farah, Afghanistan, near the Iranian border in 2008.

He believes the US pullout last summer was “too hasty” and that we should have maintained “a lower number of troops” in the country to support the Afghan Army.

“We have troops in Romania, Poland, South Korea, Kuwait, Germany, Japan” among others, he said. “We do that because we are protecting America. I think we could have done that in Afghanistan.”

Ultimately, he thinks America’s efforts on behalf of Afghan human rights and education had an impact.

“We should be proud we gave hope to these people,” he said. “Many who were educated will continue to have an influence.”

Today Schloesser works as executive vice president of Bell Textron, an aerospace manufacturer, in Washington DC.

US Army Information Technology Specialist Jessica Villarreal, 35, McAllen, Texas, therapist and advocate

Army tech specialist Jessica Villarreal counseled veterans of the Afghanistan War, helping them deal with traumatic combat experiences.

Tour of duty in Afghanistan: March 2006-December 2006

Last year, when the US withdrew from Afghanistan, Jessica Villarreal spent countless hours on the phone counseling fellow Afghanistan War veterans late into the night.

“The withdrawal was a slap in the face,” she said. “It made us question a lot of things, such as ‘Why did so many people have to die?’”

Villarreal installed cable wires and internet connections in Afghanistan and is now pursuing a doctorate in behavioral health.

As both a veteran and licensed social worker specializing in trauma, Villarreal was concerned that many fellow vets were suicidal, and volunteered her time selflessly. Many were questioning what their service had meant. She turned to Vietnam vets she knew for advice on how to help them.

Even as she assists others, she is also struggling in her personal life. Her husband Jose, also an Afghanistan vet, came back to the US with lungs destroyed by exposure to burn pits and the blast of an Improvised Explosive Device (IED).

“I was also exposed to burn pits. I came back with asthma, but my greater concern is for him. He needs a lung transplant, although we are told it won’t save his life, but might make him more comfortable,” Villarreal said.

Villarreal, who drew on Vietnam vets to help her assist soldiers in Afghanistan, said the US withdrawal led some to wonder: “Why did so many people have to die?”

“So many young women and men sacrificed our health; you can’t just get it back.”

During her deployment as a communications specialist, Villarreal was assigned to run cable wires in tight spots because she was petite. She installed internet connections and firewalls in aviators’ radios.

Today she is pursuing a PhD in behavioral health and serving as grassroots engagement director for Concerned Veterans for America (CV4A.org), a veterans’ rights non-profit.

Sgt. Major O’Neal Johnson Jr., USMC, 59; volunteer, Baltimore, Md.

Marine Corp. Sgt. Major O’Neal Johnson Jr., here being congratulated by General David Petraeus, spent a year in Afghanistan instructing its National Army.

Tour of duty in Afghanistan: September 2010-August 2011

The murder of 13 US service members by the ISIS-K terror group during the US pullout one year ago was a “moral injury” to Sergeant Major O’Neal Johnson Jr., who spent a year in Afghanistan instructing the Afghan National Army.

This past year, he has been tirelessly trying to address the suffering of his fellow Afghanistan War vets.

“The Silent Veteran” — an organization he founded to assist his fellow vets, including those who are homeless and struggling with mental health issues — is holding its first event this month connecting vets with resources for housing and healthcare.

“A lot of vets won’t reach out for help, so I said, ‘What can I do to help that silent vet?’ I try to connect them to resources.”

“A lot of vets won’t reach out for help,” said Johnson, who counsels other former soldiers through an organization he started.

One tool he cites is the Veterans Crisis Line — part of a recent federal effort to improve mental health support for veterans.

“I encourage them to dial 988 and press 1,” he said. “It’s like dialing 911 if you are having suicidal ideations or you’re in a bad way.”

In addition to his concern for vets, Johnson feels for Afghans left behind under Taliban rule. It “baffles” him that the US failed to utilize its many air bases — like Bagram, Kandahar, and Shindand — to vet Afghan allies, facilitating more transfers at the war’s end.

“You can’t just have one base with everyone rushing to get to Kabul … maybe there was a good reason but I’d like to know why they didn’t use all those air bases.”

Though Johnson laments the poor execution of the withdrawal, he ultimately supported it.

“The US was in a 20-year war and it needed to end.

“In ancient Greece, they had 20-year wars.

“There were no winners.”

This entry was written by Heather Robinson and posted on August 22, 2022 at 4:24 pm and filed under Features. permalink. Follow any comments here with the RSS feed for this post. Keywords: . Post a comment or leave a trackback: Trackback URL. */?>