Quecreek mine disaster survivors reunite 20 years after ‘miracle’ rescue

by Heather Robinson

From The New York Post

The surviving members of the miracle “Nine for nine!” miners of Quecreek, Pa. — (l-r) Blaine Mayhugh, John Unger, John Phillippi, Ronald Hileman, Robert Pugh, Mark Popernack, Randy Fogle and Thomas Foy — stand proud on the 20th anniversary of their rescue from a flooded coal mine 245-feet underground. Rob Larson for NY Post

They are older now, but still sturdy. Several walk slowly, one with a cane. They use nicknames they gave each other more than 20 years ago when their lives — entrusted to one another in their dangerous work — became forever entwined in history.

The Quecreek miners, whose story of entrapment, near-death and rescue captivated an anxious nation 20 years ago, met for a reunion on a balmy evening earlier this month at the Somerset Country Club in Somerset, Pa.

It was the first time in a decade all surviving miners had gathered, part of a weekend of celebratory events — including a Nascar race in Jennerstown, Pa., — to commemorate the 20-year anniversary of their dramatic story.

Wearing polo-style shirts, casual shorts and jeans, they stood in a Pennsylvania field, birch trees behind them, joking with a photographer and each other. The youngest, Harry “Blaine” Mayhugh, 51, took more than his share of ribbing: “Loosen up, movie star!”

The miners were trapped for three days deep under the earth in Pennsylvania coal country. The photo shoot above marks the first time in a decade they have come together. Rob Larson for NY Post

From July 24 to July 28, 2002, less than a year after the terror attacks of Sept. 11 horrified the world, a smaller news story gathered force in this country: the tale of nine miners trapped hundreds of feet below ground, their oxygen supply dwindling as the water rose around them.

The nation prayed for these men in Pennsylvania’s coal country for over three days as their families gathered in a fire station. Leslie Mayhugh, who is married to Blaine and is the daughter of miner Thomas “Tucker” Foy, 72, recalled her desperation at the time. “There were preachers, doctors and counselors in the fire hall saying, ‘You’ve got to keep positive,’ but I kept thinking, ‘I can’t lose my dad and my husband in the same day.’ Our two little ones, seven and eight years old, asking where their dad was and their Pappy Tom were. We kept praying. I had the kids go to my mom’s house [because] we didn’t want them at the fire hall if the news was bad.”

Loved ones pray near the mine on July 25, 2002, after a flood left the nine men trapped and faced with an early death. AP

Around 3 o’clock on July 24, the miners had reported for a typical day’s work, digging for coal used in power plants to make electricity. All was well until just before 9 p.m., when they cut into an abandoned mine, releasing 150 million gallons of water into Quecreek. (It was later discovered their employers had supplied them with outdated, inaccurate maps).

As the water burst through, Dennis “Harpo” Hall, the shuttle car operator, jumped on a phone to warn others working nearby. Thanks to Hall, a separate crew of nine miners made it out safely.

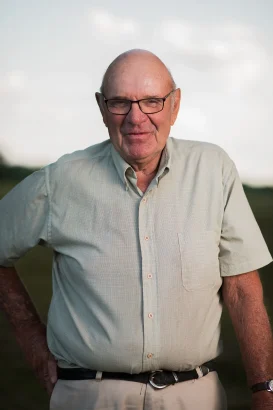

Miner Robert Pugh was among the last miners to be rescued from the shaft. He said they survived though their faith in each other — and in God. “There was nine of us,” Pugh told The Post, “and God was the 10th man.” Rob Larson for NY Post

But the remaining nine were trapped 245 feet below ground. Scrambling to find viable exits, they realized all were flooded so they huddled at the highest point they could reach. Rising water knocked out the phone line, leaving them with no way to speak to anyone outside the mine. For eight hours, they vomited and gasped for breath as oxygen dwindled. Said Miner Robert “Boogie” Pugh, 70: “I figured we were done for.”

But at 2:50 a.m., they heard a blessed sound: drilling. “You could hear them upstairs working,” said Pugh. “We had nothing else but to sit there and pray and hope for the best. We were praying hard.”

Miners Larry Summerville (left) and Doug Custer hug at the surface. They were lucky enough to escape early after their fellow miners alerted them to the flood. AP

The miners who escaped earlier had notified authorities. Under the leadership of then-Pennsylvania Gov. Mark Schweiker, a plan was hatched to pinpoint the exact spot to drill through 245 feet of rock and plumb in a pipe that would bring the men fresh air.

At 5:10 a.m., the pipe punched through the rock. Overjoyed, the miners beat on the steel pipe nine times to signal they were all alive.

But their ordeal was far from over.

A rescue worker listens as he holds a microphone cable and hears voices of the nine trapped miners at Quecreek. REUTERS

For the next two and a half days, as hundreds of emergency responders worked round the clock to drill a rescue shaft and pump out millions of gallons of water that threatened to completely flood the mine, the miners reassured each other to stave off panic.

“One guy said, ‘I’m gonna get out of here now!’” said Pugh. “We calmed him down . . . We told him, ‘You can’t go nowhere . . .take it easy. If it comes to it, we will all drown together, that’s all.’”

It took 45 hours of drilling through hard rock for rescuers to reach the trapped miners. Survivor John Unger said the men “talked about family and friends, what we would do if we got out.” Rob Larson for NY Post

“I prayed to God he’d give me the strength to accept whatever was his will,” recalled miner John “Ung” Unger, 72. He added, “We knew each other well enough to know we’d support each other.”

They rationed the lunches and thermoses of water they had brought with them for just one day of work. A corned beef sandwich that one man’s wife had packed was divided nine ways. Slowly, the lights on their hard hats burned out one by one.

They “talked about family and friends, what we would do if we got out,” said Unger.

“There was a lot of silence, too, everyone in his own thoughts,” said miner Ronald “Hound Dog” Hileman, 69. “Everybody done a lot of prayin’, that’s for sure.”

All wet in the bone-chilling cold, the men lay close together for warmth.

Rescuers watch as a drilling operation unfolds. It would take two and a half days to reach the men. REUTERS

“One would turn over and we would all have to turn over because you’d be breathing in your buddy’s face, and it was so cold,” recalled Pugh.

There was also pain because the men were positioned on top of coal seams, or parts of the mine where hard coal is embedded within rock.

At one point, the drilling stopped. “I was thinking I’d rather have died of no oxygen than drowning,” Pugh said.

The slim yellow capsule used to reach the trapped miners was tested for safety by local firefighters before being lowered into the shaft drilled hundreds of feet underground. REUTERS

Even as the drilling resumed, the men began to lose hope. In water to their chins, several of them agreed to tie themselves together to help rescue teams to find them in the event of their deaths — and also to support each other.

By the fourth day, in water to their necks, the men wrote goodbyes to their families on shreds of cardboard, using a pen belonging to their boss, Randall Fogle, 68. They put the notes in a lunch pail with a water-tight lid, securing it with electricians’ tape, where rescuers could find it.

“You know you’re at the end of the line when you’re writing your family a letter telling them, ‘Goodbye, don’t worry about us, we’ll be in a better place,’” said Mayhugh.

Ronald Hileman said prayer was a constant for the trapped miners during their time underground. “There was a lot of silence, too,” he added, “everyone in his own thoughts.” Rob Larson for NY Post

Finally, at 10:15 p.m., after more than 45 hours of drilling, the rescuers’ drill broke through rock, creating a rescue shaft. A narrow yellow rescue capsule was lowered to lift the men out. “We had half smiles on our faces thinking, ‘We may get out of here,’” recalled Pugh. “We were all happy inside, but we weren’t celebrating yet.”

The miners agreed on who would be rescued first.

“The boss went first because he was having chest pains,” said Unger.

They decided on who would go next: those in fragile health, younger men, and those with young children.

Crewmen cheer as the final miner is pulled to the surface from a shaft some 245 feet below, where water had reached up to the stranded men’s necks REUTERS

The last out were Pugh and Mark “Mo” Popernack, 61.

“I told Mo, ‘Go ahead, I’ll be the last one,’” recalled Pugh.

“Mo said, ‘Boogie, you go.’

“I said, ‘Go, you be with your kids, you’ve got younger kids.’

“Mo said, ‘You go.’

Blaine Mayhugh was the youngest of the trapped miners — stranded underground along with his father-in-law Thomas Foy. Mayhugh’s wife tried hard to shield their two young children from the full severity of the situation.Rob Larson for NY Post

“So I finally said, ‘OK, I’m not going to argue. I’m gettin’ the hell outta here!’”

When every single last man had reached the surface, their families, who were watching the rescue broadcast on a TV that had been brought into the fire hall, let out a giant cry: “Nine for nine!” That joyous outburst reverberated across the airwaves at a time when Americans longed for hope.

“The teamwork is what I recall,” said Schweiker, who now serves as senior vice president of Renmatix, a biotech research company, and attended the miners’ reunion. “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. That’s a lesson that’s timeless, even in 2022.”

Rescued miner Blaine Mayhugh speaks to reporters afterward as wife Leslie cries tears of relief. Her father, Thomas Foy, also made it out safe, after Leslie had prayed not to “lose my dad and my husband in the same day.” AP

Pugh said the experience made him a better man.

“God gives you a second chance and you try to make the best of it,” he said. “At one time, I used to run over a possum and not think about it. Now I go around them . . . I respect life much more.”

Today, the Quecreek mine is closed and just eight men survive. Dennis “Harpo” Hall died this year on May 13 at 68.

Thomas “Tucker” Foy reflects at the sealed rescue shaft last week. The mine permanently closed in 2018. AP

“Harpo would’ve wanted to be here,” Mayhugh said wistfully, looking at his fellow miners gathered before sunset. Standing with his wife, Leslie, and father-in-law, Tom, in the breezy evening, he added, “I truly believe it was a miracle.”

At a time of division in America, the rescue of all nine of the miners stands as a testament to the power of faith, unity and cooperation.

“So many good people prayed for us,” said Pugh. “I never knew we had so many good people in the world.

“There was nine of us, and God was the 10th man,” he added. “If you’re down and out, don’t give up. Don’t quit.

“I never believed in miracles.

“Until I ended up being part of one.”

This entry was written by Heather Robinson and posted on August 6, 2022 at 11:47 am and filed under Features. permalink. Follow any comments here with the RSS feed for this post. Keywords: . Post a comment or leave a trackback: Trackback URL. */?>