Wisdom of Heroes: 13 WWII Veterans Give Advice to Young Americans

by Heather Robinson

From The New York Post

WWII veterans, including Charles Shay (main photo) standing on Normandy Beach, where he stormed and now lives, reveal their war stories and advice for today’s youth.

This may be a final opportunity to hear from them: men and women of grit, resourcefulness, and courage who saved the world for future generations of Americans.

World War II veterans alive today, 80 years after humanity’s worst conflict, include minority Americans who fought Nazi racism, despite Jim Crow laws in their own imperfect nation. They loved their country, and some, including civil rights leader Johnnie A. Jones Sr., harnessed skills gained overseas to push for change at home.

A number are centenarians. Many stress unity, so essential in achieving victory. According to codebreaker Julia Parsons: “Everyone wanted to do something. And everyone did.”

As Americans emerge from upheaval amid the global pandemic and a deep political divide, the wisdom of these vets is more needed than ever. Fortunately, this Veterans Day 2021, these elder warriors can still speak to us, and we still have a chance to listen . . .

Charles Shay, a Penobscot Native American, was drafted at 19 and had scarcely left Indian Island, Maine.

Amelia Kunhardt/Portland Portland Press Herald via Getty Images

Charles Shay, Army Medic, 97, Normandy, France

When Shay, a Penobscot Native American, was drafted at 19, he had scarcely left Indian Island, Maine. “I never knew at that time what I was destined to experience.” He recalls his mother traveling to New York to wave to him as his ship, the RMS Queen Elizabeth, set sail for England. “My father had to work so he stayed in Maine, but he was there in spirit.” A freshly trained medic, Shay landed with the first wave at Omaha Beach on D-Day, the largest seaborne invasion in history, credited with hastening Nazi Germany’s defeat. Coming ashore from landing boats weighed down by machine guns and ammunition, many men drowned. Others made it to the beach and were killed in a hail of gunfire. In water to his chest, using obstacles the Germans had placed as protection from gunfire, Shay scrambled up the beach with his medic’s bag and began treating the injured. (“I found myself a place to work on higher ground.”) Administering morphine and applying antiseptic and bandages, he noticed wounded men piling up along shore, the tide rising. (“I saw . . . they would drown.”) Running back to shore, he turned them on their backs and dragged them to higher ground. Bullets whizzed past; he was untouched. He still wonders why. Among the wounded was friend and fellow medic Edward Morozewicz, whose injuries were past help. “We said goodbye.” For his bravery that day, Shay received the Silver Star and the Bronze Star. Shay pursued a career as an Air Force medic, and in 2009, successfully lobbied the state of Maine to establish Native American Veterans Day. Affinity for the French and deep connection to Normandy, where in 2007 he received the Legion d’Honneur, and where he still conducts ceremonies to honor the dead, prompted him to retire there.

His advice: It was our country originally, and even though Native Americans didn’t have as many rights as other citizens, we were still fighting for our country. For younger people considering military service, it’s not a bad life. I wish you good luck.

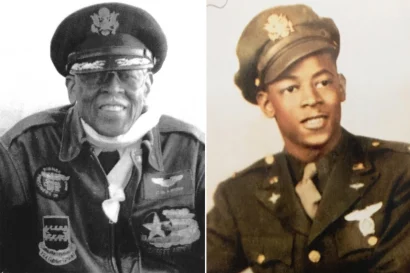

Alexander Jefferson, Army Fighter Pilot, 100 on Nov. 15, Detroit, Michigan

When Alexander Jefferson was shot down over Nazi-occupied Southern France on Aug. 12, 1944, he’d never parachuted before, though he’d flown 18 combat missions with the 332nd fighter group, part of the famed African-American pilots and support personnel who became known as the Tuskegee Airmen. Jefferson remembered to let the plane pass him before pulling the ripcord. (“Otherwise the parachute can get tied up in the plane and you’ll get dragged to your death.”) Bruised and scraped, but with “nothing broken,” he landed — in a tree. Hearing German, “being black,” and knowing the Nazis’ racism, “I said, ‘Oh, brother, here we go . . . ’” Of his eight months’ captivity with fellow American pilots in desegregated quarters, he remembers decent food from the Red Cross and adequate medical care. He and fellow pilots visited Dachau immediately after the liberation; he remembers piles of bodies. “Man’s inhumanity to man . . . I can’t even describe it,” he said. “Everything you hear is true.” Jefferson became a grade-school science teacher, assistant principal and author of a memoir, “Red Tail Captured, Red Tail Free.”

His advice: No place is going to be perfect, so love your country and preserve democratic life here. Keep your nose to the grinding mill, get an education, and vote!

Nell Bright towed targets behind B-25 and B-26 bombers to help the men practice shooting using live ammunition.

Nell Bright, Pilot, 100, Salt Lake City, Utah

Born and raised near Amarillo, Texas, Bright flew in an open cockpit WWI-era plane with her dad when she was 8, and vowed to one day be a pilot. At 19, she read about Jacqueline Cochran, the famous aviatrix who ran and helped establish the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) program, and applied. Mostly in their late teens and early 20s, the WASPs were female volunteers who took military flying jobs in the United States to free up men for overseas combat during WWII. A pilot’s license was required; of the 25,000 women applicants, 1,879 were accepted and 1,074 got their wings. Bright flew strafing missions in the desert. She flew twin engine beach airplanes, training male pilots to use searchlights. She towed targets behind B-25 and B-26 bombers to help the men practice shooting using live ammunition — one of the more dangerous exercises. “We couldn’t believe we were getting paid to fly the airplanes we wanted to fly,” she recalled. “Many of us, during the Depression, did without lunch to pay for flying lessons. We wanted to help our country.” When her older brother, an Army pilot who’d been stationed in Italy, was discharged, she got permission to fly him home to Amarillo. “He said, ‘Oh, no, I’ll take the bus,’ ” she recalls. “Little sister couldn’t do anything.” She flew him home anyway.

Her advice: Use your common sense.

Sleeping in foxholes, Meacham developed a 105 F fever and was evacuated by plane.

John Chapple/www.JohnChapple.com

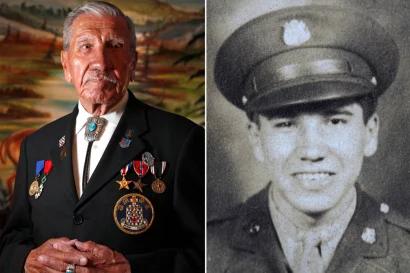

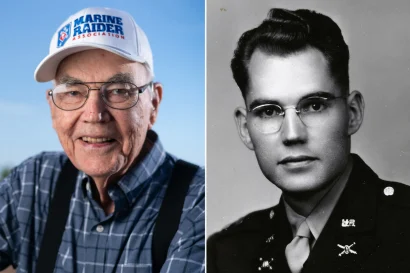

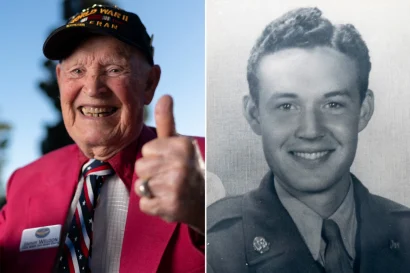

Chuck Meacham, Marine Raider, 96, Gig Harbor, Washington

Meacham served for two years as a US Marine Raider in the battles of Guam, Bougainville, Emirau, and Okinawa. Trained in beach and ocean landing, artillery, and hand to hand combat, Raiders endured grueling physical conditions. On Bougainville, Meacham evaded Japanese snipers hiding in coconut trees, and took turns with a fellow Marine to hold the other’s head out of swamp water so each could sleep. On Okinawa, Raiders traversed 25 miles a day on foot, culminating in a three-hour firefight at Montobu Peninsula. (“In our firefights there were … no enemy survivors.”) Sleeping in foxholes, Meacham developed a 105 F fever and was evacuated by plane (“I opened my eyes and saw a flight nurse … I thought I’d died and gone to heaven”). He went on to a distinguished career: US Commissioner of Fish and Wildlife. He recently helped raise funds for a school building on the island of Tulagi, where Marine Raiders first came ashore in the Guadalcanal campaign and natives helped US troops take back their island (“If the Japanese found out they were helping us, they’d kill them, so we are thanking them.”)

His advice: Be a Christian. Get educated. At that time, to fight was our duty and we did the best we could.

After the war, Weldon attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London.

Oliver Chapple/www.JohnChapple.com

Jimmy Weldon, Army Combat Engineer, 98, Burbank, California

Serving with the combat engineers under Gen. George Patton in World War II, Weldon’s squad helped clear minefields, build pontoon bridges, and liberate the Buchenwald death camp. He remembers seeing emaciated people lying side by side on slabs, “them reaching out and saying ‘Thank you.’ ” Also, “Hundreds of bodies thrown into cubicles nude like animals. I thought, ‘How is it possible?’ I was there and it was worse than history could ever depict.” After the war, Weldon attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, and became a voice actor and ventriloquist known for portraying Yakky Doodle and other Hanna-Barbera characters on “The Yogi Bear Show.” He established a nonprofit organization, the Center for Youth Patriotism, to promote civic pride in California public schools. He also authored the motivational book “Go Get ’em, Tiger!”

His advice: Don’t let anyone step on your attitude. Move on quickly to something good! If you tell a woman she’s beautiful and thank her for making dinner, she won’t say, “Stop it!”

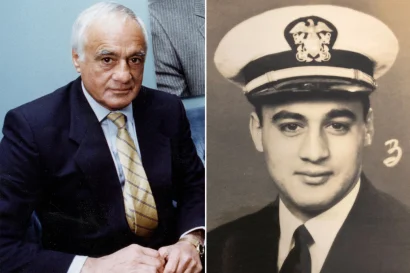

Francis Bellotti recalls JFK helping him by “having his guys put up my signs” when he ran for lieutenant governor in 1962.

Barry Chin/Getty Images

Francis “Frank” Bellotti, Navy Scout and Raider, 98, Boston

The last surviving member of his squad that stormed the beaches at Normandy, Bellotti trained for amphibious warfare with the Navy Scouts and Raiders. Precursors to today’s Navy SEALs, they specialized in underwater demolition and small arms operations, including clearing beaches of landmines and barbed wire so that invasions could take place, while remaining undetected by enemy forces. Bellotti says details of his missions are still classified. A colleague and personal friend of John F. Kennedy, Bellotti remains upset with himself for clearing out his desk of personal letters from JFK before the president’s assassination. He recalls JFK helping him by “having his guys put up my signs” when Bellotti ran for lieutenant governor in 1962, and sitting with JFK in the Massachusetts Commonwealth Armory a few weeks before the assassination. (“He was what a president should be. I was in awe of him.”) He stayed behind in Boston the day of JFK’s funeral to eulogize the slain president to the thousands mourning at the Massachusetts Statehouse. (“I felt I was needed more there.”) Bellotti eventually served as lieutenant governor and attorney general of the state of Massachusetts.

His advice: Appreciate your country. I don’t know if enough younger people do. I went to law school on the GI Bill and they paid my tuition and books. In what other country could that happen?

George Hardy, Army Fighter Pilot, 96, Sarasota, Florida

A highly decorated member of the Tuskegee Airmen, the first black aviators in the US Army, Hardy flew 21 combat missions over Germany in World War II. Guarding American bombers, he “chased a few” Nazi fighter pilots away. Taking his cue from Benjamin O. Davis Jr., founder and commander of the Tuskegee Airmen, Hardy viewed himself as a protector. (“Davis said, ‘Do not leave the bombers.’ We stuck with them.”) Wishing to serve in the Navy with a beloved older brother, Hardy learned it was segregated and he’d have to work in food service. So he set his sights on what was then called the Army’s Tuskegee Experiment (“I said, ‘I don’t want race to be a problem’ . . . I passed all the tests.”) Just 17, he focused on listening and following instructions: “I applied myself . . . Getting off the ground, into the clouds — it was lovely!” He doesn’t recall feeling scared; rather, empowered: “I wasn’t the big guy growing up, but the skinny guy” — which helped make him an ideal fighter pilot: “They’d pick bigger guys for the twin engine planes,” whereas “fighter pilots were smaller guys . . . Single engine; you control everything.” Training to fly P-51 Mustangs (which lent the 332nd its “Red Tails” nickname for the color on its planes’ tails), Hardy recalls a friend letting him drive his luxurious LaSalle back to the barracks in Walterboro, SC. The hitch? The newly minted fighter pilot had never driven an automobile. Hardy went on to a distinguished career as an Air Force combat pilot.

His advice: Avoid extremism. Listen.

Hershel William wassent to the South Pacific — where he fought in the Battle of Guam, then the Battle of Iwo Jima.

AP

“Oldest Living Medal of Honor Recipient”

Hershel “Woody” Williams, 98, Combat Marine, Charleston, W. Virginia

Hershel “Woody” Williams is the last living WWII veteran recipient (and the oldest living recipient) of the Medal of Honor — the military’s highest decoration for valor in combat. In 1943, as a Marine infantryman, Williams was trained in demolition and using flamethrowers. Sent to the South Pacific, he fought in the Battle of Guam, then the Battle of Iwo Jima, where he fought Japanese firing on US soldiers from reinforced concrete pillboxes, then vanquished enemy soldiers who rushed him with bayonets. Fighting hand to hand for over four hours, he helped give the Marines a foothold on the day the US flag was raised at Iwo Jima. After he was presented the Medal of Honor by President Harry S. Truman (pictured) on Oct. 5, 1945, Williams went on to serve in the Marine Corps Reserves and as a Veterans Affairs counselor. On March 7, 2020, a Navy warship, The USS Hershel “Woody” Williams, was named after him.

His advice: So many of our citizens have sacrificed their lives for the precious gift of freedom. If we do not preserve that freedom it will go away.

“The Last Tuskegee Airman”

Lieutenant Colonel Carl C. Johnson, Army Fighter Pilot, 95, Ashburn, Virginia

As a boy, watching the mail plane fly down the Ohio River from his hometown of Bellaire to Cincinnati, Carl C. Johnson was fascinated by aircraft. But it wasn’t until high school, when he and a football buddy asked about enlisting in the Army, that he thought of becoming a pilot. “My friend, who was white, received a notification, and they didn’t call me,” recalled Johnson. “I first then felt discrimination.” In college at Ohio State, he was drafted and tapped for what was then called the Tuskegee Experiment, ultimately known as the Tuskegee Airmen. Comprised of almost 1,000 pilots and many thousands more support personnel, this unit escorted mostly white bomber pilots in combat, with an above average success rate, at a time when the US military was segregated. Training was rigorous, and Johnson was one of 12 in his class of 119 to make it to phase four. He completed his training in a special program for pilots from China, then a United States ally. After graduation, along with his Tuskegee Airman wings, Johnson received “Chinese wings” from Chinese President Chiang Kai-shek for helping communicate instructions to the Chinese flying B25 twin engine planes. (“I was an instructor for them, more or less,” he recalled.) A decorated Army pilot in the Korean and Vietnam wars, Johnson later became deputy director of the Pittsburgh International Airport in the 1970s.

His advice: I’d stress education. You’ve got to prepare yourself. Try to be open-minded. That’s difficult, but important.

Julia Parsons, Navy Codebreaker, 100, Forest Hills, Pennsylvania

World War II brought Julia Parsons a unique opportunity. After finishing college at Carnegie Mellon (then Carnegie Tech) in her hometown of Pittsburgh, Parsons had wished to be an engineer. (“They just laughed at me; they didn’t offer women many opportunities back then.”) Instead she joined the US Naval Reserve’s WAVES, Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service. After acing an aptitude test, the Navy sent her to Washington, DC, to serve as a codebreaker. “Someone asked if anyone knew German,” Parsons recalled. “I raised my hand, said yes, I’d taken two years of German in high school.” While that got her into the top-secret unit, she rarely employed her German in cracking codes; rather, the work was more mathematical, and involved using an early computer. With American ships bringing crucial supplies to England being sunk by German U-boats, the work was urgent. “It was our duty to break the code and find out what the messages from German subs were saying,” Parsons recalled. “Sometimes we could, sometimes we couldn’t.” Work was strictly classified; she couldn’t tell her family or friends what she did. “I didn’t tell my husband until the late 1990s. He was annoyed . . . but I said, ‘What difference does it make now?’” After the war, she became a wife, mother, and high school English teacher.

Her advice: I just wanted to do something, everyone wanted to do something, and everyone did. It’s amazing what a country can do when people are united.

Paul Cohen has remained active in World War II veterans organizations and in 2013 was named Los Angeles County Veteran of the Year.

MediaNews Group via Getty Images

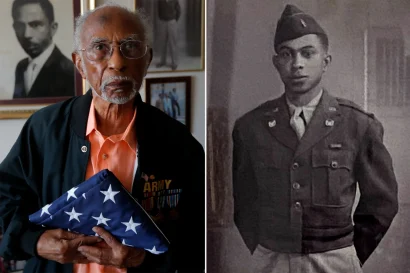

Paul Cohen, Army Forward Observer, 100, Los Angeles, California

Trained for amphibious warfare, due to considerable anti-Semitism, Cohen transferred to a cannon company as a forward observer. His role was to go to an observation point on higher ground with a radio officer to report what he saw and call orders to the tanks. (“They called me ‘Jew boy,’ but in the new company it wasn’t derogatory. In the old company they’d say, ‘You’re Jewish; you’re supposed to be in an office with a typewriter.’ I said, ‘First of all, I can’t type, and second, no job is too tough for me.’ ”) On Okinawa, he and his platoon leader, James Owens, went into a village to assess enemy presence when Japanese forces let loose with machine gun fire. (“It lifted me off the ground.”) Owens, bleeding profusely, was unable to walk; Cohen carried him back through heavy fire to a first aid station (“At 24 I could lift a building”), earning Cohen the Bronze Star for bravery. He has remained active in World War II veterans organizations and in 2013 was named Los Angeles County Veteran of the Year.

His advice: Think before you vote. What’s going to be good for you? Will it benefit your future, or harm your future?

Joseph Dona, Navy Gunner, 100, Johnstown, Pennsylvania

Born in Abruzzi, Italy, Dona immigrated with his family to the United States at age 3. At 19, as World War II broke out, he received a letter from Mussolini asking him if he wanted to serve in the Italian Army, but, loving America, he adamantly refused. “I said, ‘They’re not gonna draft me.’ I joined!” He served as a coxswain and gunner on the USS Suwannee, a Navy aircraft carrier that provided escort to supply ships supporting the Marines on Guadalcanal, and fought in 14 battles, including the Battle of Leyte Gulf, where his ship was hit by a kamikaze pilot, knocking Dona out and earning him a Purple Heart. (“The kamikazes, they came right down. We manned the guns. I don’t know if I shot one down, I’m sure I helped. Next thing you know, I’m on a pile of guys. And they’re dead.”) He remembers medics, lacking morphine, offering him wine. He recalls good times amid the terror, including listening to Tokyo Rose, a Japanese propaganda broadcast featuring American songs that tried to hurt morale, crooning: “Boys, guess what your wives and girlfriends are doing now?” Dona, who met his wife of 72 years, Marie, a codebreaker, before shipping out, remembers he and his buddies weren’t easily spooked: “We said, ‘She’s probably having more fun than me!’”

His advice: Love your country.

Johnnie A. Jones Sr., Army Warrant Officer, 102 on Nov. 30, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

The second African-American warrant officer in the US Army, Jones was drafted while studying at Southern University in Baton Rouge, and commenced his duties in desegregated quarters in New Orleans. Transferred to South Carolina, assigned to a separate “filthy” barracks, he made his case to Brigadier Gen. James T. Duke, scion of a North Carolina tobacco family: He and white officers had bunked together in New Orleans. Duke arranged for Jones to stay at a boarding house in Charleston instead. Jones recalls that time fondly. He saw Ella Fitzgerald, and Duke occasionally came for lunch. On D-Day and at the Battle of the Bulge, Jones managed equipment, supplies, and fellow soldiers’ belongings; he returned personal effects to men who survived and to the families of the fallen. (“I managed thousands.”) In 2021, he belatedly received the Purple Heart for injuries sustained at D-Day when his ship, the Francis C. Harrington, hit a mine (“I went up in the air sky high, and came crashing down, mixed with the enlisted men.”) Jones was proud to serve (“I did everything I could for our country”) but was dismayed on return. (“As soon as I crossed the Mason-Dixon Line I heard, ‘Go to the back, boy’ . . . I had forgotten about segregation.”) An attorney, his long career included representing the architects of the Baton Rouge Bus Boycott and a term as a Louisiana state representative.

His advice: There were times I felt like blowing some heads off, but I’d say don’t do it. Stay in school and follow the principles of Christianity.

This entry was written by Heather Robinson and posted on November 8, 2021 at 6:45 am and filed under Features. permalink. Follow any comments here with the RSS feed for this post. Keywords: . Post a comment or leave a trackback: Trackback URL. */?>