What Mr. Rogers Understood About NYC Neighborhoods

by Heather Robinson

From The New York Post

Mister Rogers would’ve been sad about the way we treat each other.

That thought occurred to me as I sat in a Kips Bay theater one afternoon last week, escaping the heat and watching “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” The documentary follows the career of Fred Rogers, host of the popular kids’ TV show that debuted in Pittsburgh in 1968 and became a staple of national public television for decades.

In a summer of the usual blockbusters, this heartfelt documentary has been quietly catching on. With a 100 percent increase in box office sales in its second week of release, it appears to be generating enthusiasm among a small but loyal following of adults who, like me, grew up watching “Mister Rogers Neighborhood” in the 1970s.

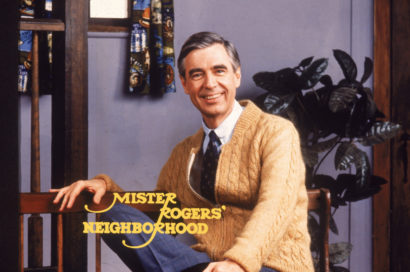

For those who missed it, when Mister Rogers donned his trademark red cardigan and sang, “You are my friend, you are special,” and talked about feelings, it seemed like he was speaking directly to us, and understood our secrets.

He also talked, and sang, a lot about neighborhood.

Mister Rogers’ neighborhood featured a trolley, a paper mache-looking castle and a cast of friendly characters — some of them sock puppets in a neighborhood of make-believe, others “real” people, like the postman Mr. McFeely, gentle Lady Aberlin and Police Officer Clemmons (played by a gay black man named Francois Clemmons, who speaks in the documentary about his great friendship with Rogers, who was a Presbyterian minister).

Neighborhood wasn’t anything fancy or even all that exciting; it meant “a place that, at times you felt scared or unsafe, would take care of you,” according to one of the show’s producers.

After the lights came on, there weren’t many dry eyes in the theater, including my own.

In the documentary, when she was asked what she believed her husband, who died in 2003, would think or do about the state of today’s society, Mister Rogers’ widow Joanne replied, “I think he would be trying to mend the split,” and added, “I think he’d be trying to find a way to do something positive.”

Toward the film’s end, Mister Rogers says, “Let’s make goodness attractive in this next millennium . . . I’m not talking about Pollyanna stuff. I mean . . . people caring about each other rather than knocking each other off.”

This country could take a cue from Mister Rogers.

We hear a lot about people’s exhaustion with partisan politics and social media, but as a society we seem addicted to both.

Political correctness, theoretically intended to salve some of these wounds, often turns out to be used as a partisan weapon. Mister Rogers’ lessons about simple kindness have fallen by the wayside. On platforms like Twitter, viciousness gets rewarded with “likes” and mob behavior is incentivized.

And in coffee shops, people stare at their computer screens and smartphones, oblivious to the actual humans around them.

But New York is still a city of neighborhoods. Although things move fast, if you look up now and again from the virtual world, you can see the beauty of the real one, including in the faces all around you. (The parks are especially great for people watching.)

Turns out, humans have always gravitated toward neighborhoods, because we are social creatures, and without social connection, we suffer, say experts.

“People who practice being good neighbors do tend to be happier,” said Manhattan therapist Linda Barbanel. “Smile and say good morning, hold the elevator door open when you see people running to get it, pick up a little trash. We are social animals, and unless we practice being social, we’ll just be animals.”

At a time when many fall into the trap of envying others’ too-perfect-seeming Facebook pages, or pile on the latest Internet scapegoat, Mister Rogers’ insight that people grow and change when they are treated with total acceptance and love, that a neighborhood is a place where people support each other, may seem more make-believe than real.

Here’s the bright side: New York is a city where people of all backgrounds live in close proximity, and our neighborhoods are not virtual, but real. Life is not unfolding on a computer screen, but on our city blocks. Let’s share a smile, a glance, a kind word.

In “Open City,” Teju Cole writes of New York: “Each neighborhood of the city appeared to be made of a different substance, each seemed to have a different air pressure, a different psychic weight.” You didn’t have to tell Mister Rogers — but sometimes, the rest of us need to be reminded.