Senator Dick Lugar Departs with a Statesman’s Warning

It’s a departing statesman’s job to share what he has learned. George Washington famously cautioned Americans to take advantage of a “detached and distant situation” to “pursue a different course” from that of Europe and avoid unnecessary conflicts. Dwight D. Eisenhower warned of the dangers of military-industrial complex overreach.

Last week, following his defeat by state Treasurer Richard Mourdock in Indiana’s Republican primary, departing Senator Richard Lugar, a 36-year veteran of Capitol Hill, shared a warning that Americans of all political stripes would be well advised to heed. In conceding to Mourdock, Lugar warned, “Ideology cannot be a substitute for a determination to think for yourself, for a willingness to study an issue objectively and for the fortitude to sometimes disagree with your party and even your constituents.” He also said that if voters demand “near-total fealty from candidates to party-line ideologies …Voters will be electing a slate of inflexible positions rather than a leader.”

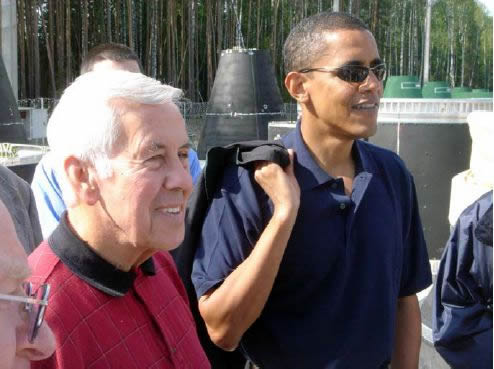

As a highly effective fighter in the Senate for security policy, Lugar co-authored the Nunn-Lugar program. This bi-partisan effort, initiated with Democratic Senator Sam Nunn of Georgia, enabled the dismantling of more than 7,500 nuclear warheads, 1,400 nuclear-capable ballistic missiles, 155 bombers, and 32 nuclear submarines in the former Soviet Union during the years following its collapse. To the extent that the Russians have not already sold nuclear weapons and WMD to Islamist terrorists, it may be due to this important program; thus, Lugar has earned an important platform from which to speak credibly about bipartisanship.

At a time when American politics have seldom been more polarized, his words about the value of moderate and independent politics are of import. When voters become increasingly arch in their insistence that candidates’ voting and governing records stack up neatly along party lines and that their past behavior and voting records cleave to rigid ideologies, the country is destined to pick its leaders from one of two polarities: conservative Republican or liberal Democrat. Come to think of it, that’s what’s happened in the last three Presidential elections, and in most Congressional elections for many years.

How’s that been workin’ out for us?

One consequence is fewer problem-solvers, and fewer politicians who work well with the best and brightest on the other side, are coming to the fore in national politics (although such “moderate” stars, like New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani and Newark Mayor Cory Booker, have achieved great results at the local level). Say what you will about Bill Clinton, he did manage some of his best work as President—welfare reform– with pressure and help from a Republican Congress. He balanced the federal budget, incorporating conservative principles in his approach. And it was President Richard Nixon, known as a hawkish conservative on foreign policy, who opened relations with Communist China.

Out-of-the box strategies have worked for many politicians and for the country. But in an era in which, for most Americans, the litmus test for a candidate is a rigid adherence to a party line (and status as a “true liberal” or “true conservative,”) our country is less likely to elect outside-the-box thinkers or those who can incorporate the strongest ideas from across the political spectrum to problem-solve.

Oftentimes in politics, as in life, ideological purity goes hand-in-hand with stubbornness and extremism—traits that can enable those who possess them to spark revolutions or confront injustice. But in governance–as in day-to-day life–it tends to be the moderates who ensure that the center holds, that relationships are stable, and that work gets done.

Given that the country’s past two Presidents have come from extreme sides of the political spectrum and so have most members of Congress, perhaps it would be wise to heed the departing words of a Senator who spearheaded solid and far-sighted security policy by reaching across the aisle and working with the other party. Good ideas come from both sides; effective politicians grasp this simple truth and can exploit it.

At this troubled juncture, it may well be the wiser course to set aside the quest for some perfect ideological purity and choose instead as leaders realists with proven track records of working well with others—including those on the other side of the aisle.

This entry was written by Heather Robinson and posted on May 27, 2012 at 11:59 am and filed under Commentary. permalink. Follow any comments here with the RSS feed for this post. Keywords: . Post a comment or leave a trackback: Trackback URL. */?>