Sharansky calls for support for reformers; Alusi cautions U.S. troop withdrawal a blow to human rights in Iraq; Havel, champion of democracy, dies

The Washington Post just ran this thought-provoking piece on the Arab Spring by former Soviet dissident refusenik and Israeli Parliamentarian Natan Sharansky. As I wrote last spring, Recent upheavals across the mideast from Egypt to Tunisia to Syria can be viewed through the prism of Sharansky’s ideas on democracy and even as validation of them. But in the messy aftermath of these hopeful uprisings, some are questioning whether the Arab world can handle freedom. In this piece, Sharansky offers his thoughts.

Sharanksky, whose championing of freedom during early life led to nine years in a gulag for refusing to give up his dream of emigrating from the former Soviet Union to Israel, has always maintained that most people desire freedom. His theory of people’s behavior under totalitarianism, or “fear society,” is that while the vast majority will conform, and a few will be true believers, the majority will secretly yearn for freedom – but lack the courage to fight against the regime, which will employ brutality and other means (such as blaming external scapegoats as escape valves for the people’s frustrations) to maintain control over individuals.

Only dissidents will resist. But once a critical mass of people have managed to stand up to the regime, it will crumble. That is because totalitarian states are by definition internally weak (hence, like bullies, their need to employ vicious scare tactics and scapegoating). Lacking the internal strength which comes from the consent of the governed and from accurately honoring what is most timeless and essential in human nature, a dictatorship is a facade that will fall rapidly once enough people stand up to it.

Sharansky’s latest editorial addresses Westerners’ concerns in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, which has sadly seen “liberals’ miserable showing [in Egypt’s elections] and the military’s determination to maintain an iron grip,” leaving some to “ask whether the end of Egyptian democracy is already in sight” and “whether democracy, ‘our’ Western heritage, is really for ‘them.'”

Sharansky reminds readers that the French Revolution, too, although hailed as a victory for and advancement in human freedom and dignity, was not just exhilarating but also very ugly and bloody (and not without its cruelty). Also, the building of a civil society in France took time. To quote him more precisely: “[I]f the bloody aftermath of the French Revolution proves anything, it is that a gap exists between the moment people decide they will no longer live in a society ruled by fear and the moment a democratic society forms—a society that will protect not only ‘correct’ thinking but also the thoughts one hates.”

Sharansky goes on to argue that the West needs to actively support the true proponents of democracy in the middle east and assist them in building democratic institutions – lest the progress gained in these revolutions be lost and the societies revert to dictatorship. This latter regression is possible because dictatorships are cemented and bolstered when outside forces (such as countries that, in their desire for oil, keep the money flowing to these repressive regimes) keep them subsidized.

It seems to me that popular upheavals against totalitarianism are, while at times and places contaminated by the darker impulses in human nature, in the grand scheme still a big step toward forward, and reflect growth. The analogy that springs to my own mind is one of giving birth. No doubt for women, especially in the past, this was a terrifying, painful, messy, and violent ordeal. It is amazing they had the courage to move forward and attempt it, but in reality I suppose it was inexorable, an expression of human needs and impulses, of instincts that could not be denied. Many died in childbirth and many infants did, too.

When viewed as a stage of human development that is inexorable if not inevitable, the upheavals in the Arab Muslim world could be viewed as a kind of birth–messy, painful, at moments thrilling, dangerous, bloody. But one does not give birth to a full-grown man or woman; rather, to an infant who will need a tremendous amount of care, material support, attention, nurturing, guidance and protection. So, too, the forces of true democracy in this tumultuous, often violent part of the world need protection, nurturing, care, material support, etc. Perhaps contained within the many forces at work in the Arab Spring are the seeds of a future democratic middle east. Will we, unnerved by what appears will be a messy transition and repulsed by its ugliest elements (witness what happened to Lara Logan in Tahrir Square), turn our backs entirely and fail to separate the true champions of democracy, and the masses who could go either way, from the extremist forces in the region? Or will we seeks out democracy’s champions, as well as build and nurture democratic institutions like schools, civic institutions, and media outlets that promote democratic principles? Just as totalitarianism brings out what is lowest in human nature, so democracy–embraced by a willing and educated public–brings out the highest. Will we assist in supporting the best and the brightest in places like Egypt and possibly soon Syria, so that they can better do the difficult and wonderful work of leading their societies forward? It seems to me that, given the roughness of their neighborhoods, these leaders–who by definition are not the thuggish types–need our support more than ever.

My consideration for this point of view is only enhanced by the fact that in this editorial, Sharansky mentions my Iraqi source Mithal al-Alusi, who along with other dissidents met in 2007 with President Bush at a summit in Prague. Apparently, the dissidents told President Bush that democratic change would soon sweep the mideast.

I spoke with Mr. Alusi today (12/18/11). He is very concerned that in removing U.S. troops from Iraq, President Obama will be allowing extremists to strike severe blows to “freedom, peace, human rights, and women’s rights” in the region (more to come).

If it’s true that a gap exists between the moment people decide they will no longer live in a society ruled by fear and the moment a democratic society forms, we should be using our economic and political leverage to support the liberal forces who are trying to guide their societies across the gap–not subsidizing or supporting forces that want to go backward.

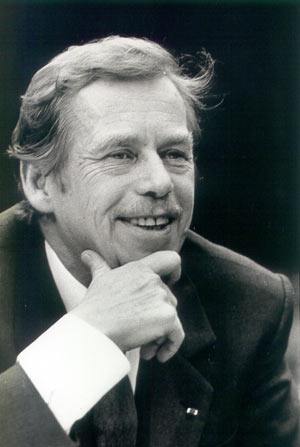

In related news, Vaclav Havel, Czechoslovakia’s former President who spent years protesting communism before becoming leader of the post-communist Czech Republic, died this week. Havel was a dissident playwright, an artist whose highest personal bliss was simply to write and listen to music (he reportedly said that was what he would have enjoyed doing most). Called by conscience, he lent his gifts to the fight for his people’s freedom. During their transition from totalitarian rule to democracy, he became a reluctant public servant–in the truest sense of the phrase. Our world sorely needs leaders like Havel–not primarily driven by ego, but by the desire to advance the highest ideals. May he rest, tell stories, and make music now in peace.

This entry was written by Heather Robinson and posted on December 18, 2011 at 11:53 pm and filed under Blog. permalink. Follow any comments here with the RSS feed for this post. Keywords: Arab-Jewish-relations, democracy, Egypt, human-rights, Syria. Post a comment or leave a trackback: Trackback URL. */?>