Pal reveals Lee Harvey Oswald’s weird, paranoid life one year before killing JFK

by Heather Robinson

From The New York Post

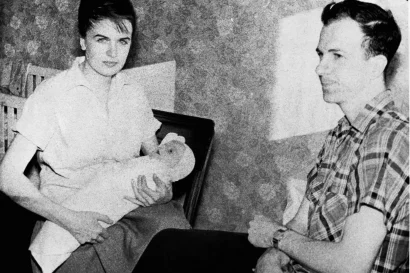

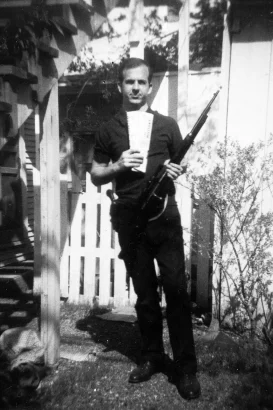

In the summer of 1962, Marina and Lee Harvey Oswald were welcomed by the “Dallas Russians,” a group that included Peter Gregory, the father of Paul Gregory. Paul became friends with the couple and recalls the future JFK assassin as an alienated loner who beat his wife. Corbis via Getty Images

When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963, graduate student Paul Gregory shared in the nation’s horror.

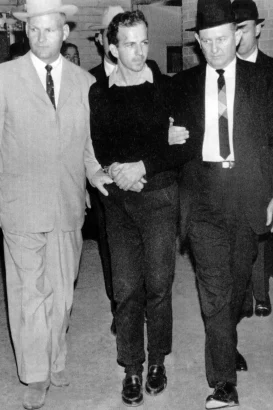

But his shock was compounded when, watching TV a couple hours later, he saw his former friend Lee Harvey Oswald in handcuffs for committing the assassination.

Even so, “within an hour, it made sense to me,” Gregory told The Post.

While Gregory had no inkling of Oswald’s plans, his former friend’s secretive nature, intelligence, grandiosity, inferiority complex and violent ways all added up to the picture of a lone-wolf assassin, he said.

“The next morning when the Secret Service came to question me, I told them, ‘I’m convinced he did it.’”

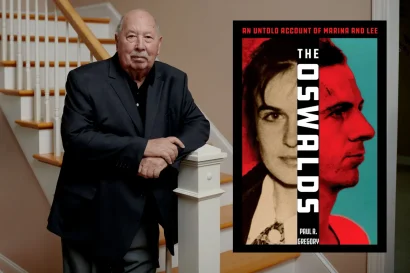

In his new book, “The Oswalds: An Untold Account of Marina and Lee,” Gregory, 81, recalls his first evening in the company of Lee and his wife, Marina, when all three were in their 20s. Now a professor emeritus of economics at the University of Houston and a research fellow at Stanford, Gregory recalls the summer of 1962 when they spent significant time together.

Despite being born and raised in Russia, Marina Oswald was surprisingly knowledgeable about the Kennedys, Gregory writes. Alamy

He remembers the Oswalds’ threadbare apartment, devoid of a television, radio, board games or even a fan. The couple owned just one recreational item: a copy of Time magazine with JFK as Man of the Year on its cover, which permanently sat on a coffee table in the home.

“That magazine was to remain in the same position on the table throughout all my visits,” writes Gregory.

The normally reserved Marina lit up speaking about both JFK and his wife, Jackie, he adds.

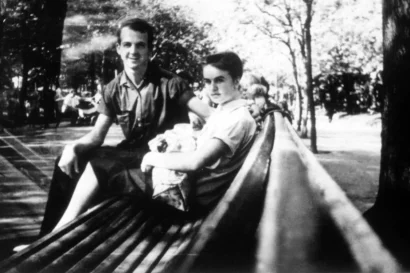

The Oswalds in a park in Russia; once in the US, Marina was described as looking like a “lost kitten” as she struggled to adjust to her new nation. Corbis via Getty Images

“I wanted to know if Marina, fresh from Russia, knew who JFK was . . . She appeared to know more than I expected,” Gregory writes.

The fact that Oswald went on to kill the man on that magazine cover seemed impossible at the time.

“As the three of us sat around the small coffee table, the thought that Lee Harvey Oswald, a year and two months later, would shoot the president whose visage was staring up at us from the cover of Time, would have struck me as the most insane of propositions.”

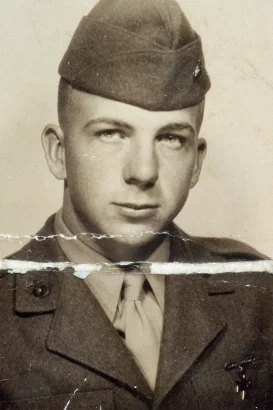

A former Marine, Lee Oswald defected to the Soviet Union, but eventually returned to live in the US. Corbis via Getty Images

In his book, Gregory recounts how his father, Peter Gregory, a successful petroleum engineer originally from Siberia, received a call from an employment agency in June 1962, asking if he would be willing to certify that a young man who wished to apply for work as a translator was fluent in Russian. Peter agreed to accept a visit from the young man at his Fort Worth office.

That man was 22-year-old Lee Harvey Oswald.

Oswald was a former Marine who had defected to the USSR and then returned to the US, while Marina was a native-born Russian living in America — a rarity at the height of the Cold War.

Pete and Elizabeth Gregory (Paul’s parents, left) in 1962 with George Bouhe, head of the Dallas Russians who tried to help the Oswalds.

Peter was part of a group of prominent local Russians — known as the “Dallas Russians” — who were “avid anti-Communists [who] considered their new home the land of milk and honey.” Nonetheless, he befriended the Oswalds.

“Remember, the Iron Curtain was impenetrable,” said Gregory. “The Fort Worth-Dallas Russians were like displaced persons” and they wished to hear from the young couple about life in the USSR.

There was also a desire to help Marina, who was, according to Gregory, a quiet, attractive young woman with the look of a “lost kitten.” Gradually the Dallas Russians became aware, especially when they saw black eyes on Marina’s face, that she was being abused by Oswald.

“When they went to parties, Marina would socialize but Lee was the embodiment of a loner, standing in a corner,” said Gregory. “He was regarded as unfortunate baggage . . . To do anything to help Marina you had to deal with him.”

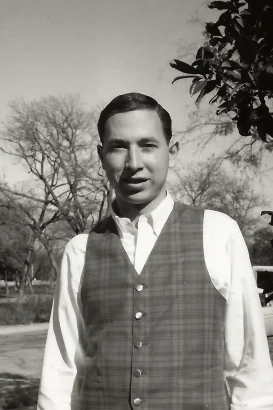

When Paul Gregory (above) saw Oswald had killed JFK on TV, “Within an hour, it made sense to me,” he said.

Oswald never got a job as a Russian translator, and he would not allow Marina to learn English. However, he permitted her to teach Russian to Gregory, which is how Marina and Gregory became friends when they were just 21.

Studying Russian with Marina biweekly, Gregory often volunteered to take the couple grocery shopping because they did not own a car or a baby carriage. The couple was not affectionate toward each other, though both appeared to love their baby, June, he writes.

Gregory describes Oswald as quiet, brooding, given to explosive, angry outbursts and evasive when questioned about his life, especially when he was asked why he had defected to the Soviet Union.

Lee Oswald poses with his rifle and two Communist newspapers in an infamous backyard photo unearthed in the investigation of JFK’s murder.

Oswald was an avowed Marxist whose sojourn to the USSR had failed, and Marina “viewed her husband’s ‘deeply held’ views with scorn,” Gregory writes. “Further, she must have been aware that such views . . . could get her and her family in trouble in the US.”

Gregory recalled driving his friends to see some of Fort Worth’s grandest “estates and mansions … that the oil wealth of Texas had built.”

Marina was transfixed, but Oswald started to lecture them about the evils of capitalism. “Marina assumed a bored air, having no interest in her husband’s commentary.”

President John F. Kennedy riding in Dallas with First Lady Jacqueline, as well as the governor of Texas and his wife, moments before doom. Bettmann Archive

Oswald’s inferiority complex appeared in various ways, such as when he burst noisily into the duplex, arms piled high with “weighty works worthy of an intellectual leftist… I suspect he orchestrated his entrance … If Lee’s strategy had been to focus on his intellectual proclivities and prowess, it worked.”

Despite being a “penny-pincher” who limited Marina to $2 a week in spending money, and just enough food to subsist, Oswald paid a typist to prepare his memoirs, which he called his “Historic Diary” and was convinced would soon find a publisher. (It didn’t).

Oswald, just moments before he was shot in Dallas in 1963, just days after the Kennedy assassination. Alamy

When good Samaritans from the Russian community gave the Oswalds a hand-me-down baby carriage, Lee accepted the gift but flew into a rage over needing charity — a pattern of freeloading and resentment typical of him that, along with his abuse of Marina, eventually made the Dallas Russians give up on trying to help him.

In November, Marina asked Gregory to come to Oswald’s brother’s house, where they were celebrating Thanksgiving, and also asked for a ride to the bus station.

Gregory did, first bringing the couple to his parents’ house, where they snacked and made “strained conversation.”

Author Paul Gregory says for years his family was ashamed of their association with Oswald. Jack Sorokin for NY Post

Then, Oswald brooded as Gregory drove them to the Fort Worth bus station. It would be the last time Gregory saw either of them.

“My next view of Lee was exactly one year later as the police hauled him into the Dallas police station as the prime suspect in the assassination of the president.”

Gregory did not reach out to Marina after JFK’s murder or Oswald’s own killing two days later at the hands of Jack Ruby, a loner who said his moral outrage over the president’s death led him to gun down his assassin.

The Oswalds owned just one recreational item in their Dallas apartment: a copy of Time magazine with JFK as Man of the Year on its cover, which permanently sat on a coffee table in the home.

“I knew she was deluged . . . so I figured the best thing was to leave her alone,” Gregory said.

In later years, the only contact Gregory could make was with Marina’s second husband, Kenneth Porter, who asked that he respect Marina’s privacy.

“He was protective and I respected his wishes, which were her wishes.”

Marina Oswald (in 1963 and in 1978) now lives near Dallas and avoids the media spotlight; she now goes by her second married name Marina Porter.

Marina and Lee Harvey Oswald had two children together, June and Rachel (who was only five months old at the time JFK was assassinated and her father was killed). June, who gave an interview to The New York Times in 1995 and has avoided the spotlight since, grew up to live an ordinary life as a mother and businesswoman. Rachel is also reportedly alive and well.

At present, Marina Porter, 81, lives a quiet life in Rockwall, outside Dallas. In response to The Post’s request for an interview, she wrote back: “I don’t want to make a comment. Need my privacy. Thank you.”

Gregory said he chose to write his book now because colleagues have encouraged him to contribute to the historical record as the 60th anniversary of JFK’s assassination approaches.

Gregory has written new book “The Oswalds” detailing his family’s unique connection to the infamous couple.

For years, in the aftermath, Gregory did not want to go public because of the potential stigma.

“Our family was ashamed of its association with Lee Oswald,” Gregory said. “Our neighbors would’ve asked, ‘What were the Gregorys doing with a communist deserter, this traitor?’ We wanted to stay below the radar.”

Although Oswald was a Marxist, the Warren Commission did not officially conclude that his primary motivation for assassinating JFK was political, but rather that he was a profoundly maladjusted, malcontented loner, who committed the act out of a desperate, sick desire to feel significant. Gregory agrees, adding that he believes Oswald’s intense, tormented relationship with Marina, and his desire to appear important in her eyes, played a role.

“If Lee Harvey Oswald [had grown up] today, he would probably have become a school shooter,” said Gregory. “He might [again] have . . . gone after a public figure, someone whose death would get him into the news.”

It’s even possible that Oswald killed JFK because the young president was seen as the ultimate symbol of American masculinity and power — and because Marina liked him.

As Gregory said, “he knew that by killing JFK, he would wound Marina sorely.”

This entry was written by Heather Robinson and posted on November 20, 2022 at 12:55 pm and filed under Features. permalink. Follow any comments here with the RSS feed for this post. Keywords: . Post a comment or leave a trackback: Trackback URL. */?>